Monster sharks have returned to the Jersey Shore.

Is it a nightmare or a new golden age?

By Adam Clark | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

He leaps from a dock on a sweltering July afternoon and splashes in a creek with three chilling words.

Watch me float!

His name is Lester. He’s 11 years old. He never sees his killer coming.

Lester suddenly shrieks. His flailing body bobs down, then up, then down again. Matawan Creek runs red with his blood.

The boy is the third person brutally killed in New Jersey waters in 12 days. He won’t be the last.

Five are attacked in total. Four perish gruesomely. Full-blown hysteria grips the Eastern seaboard.

Desperate men hurl dynamite into Matawan Creek. Stoic women stand guard, shotguns pointed at the water. What’s left of Lester’s shredded body surfaces two days later.

The frenzy of violence in 1916 changes everything, a seminal moment that still haunts bathers around the world.

What kind of savage, cold-blooded monster lurks beneath the surface of the blue unknown?

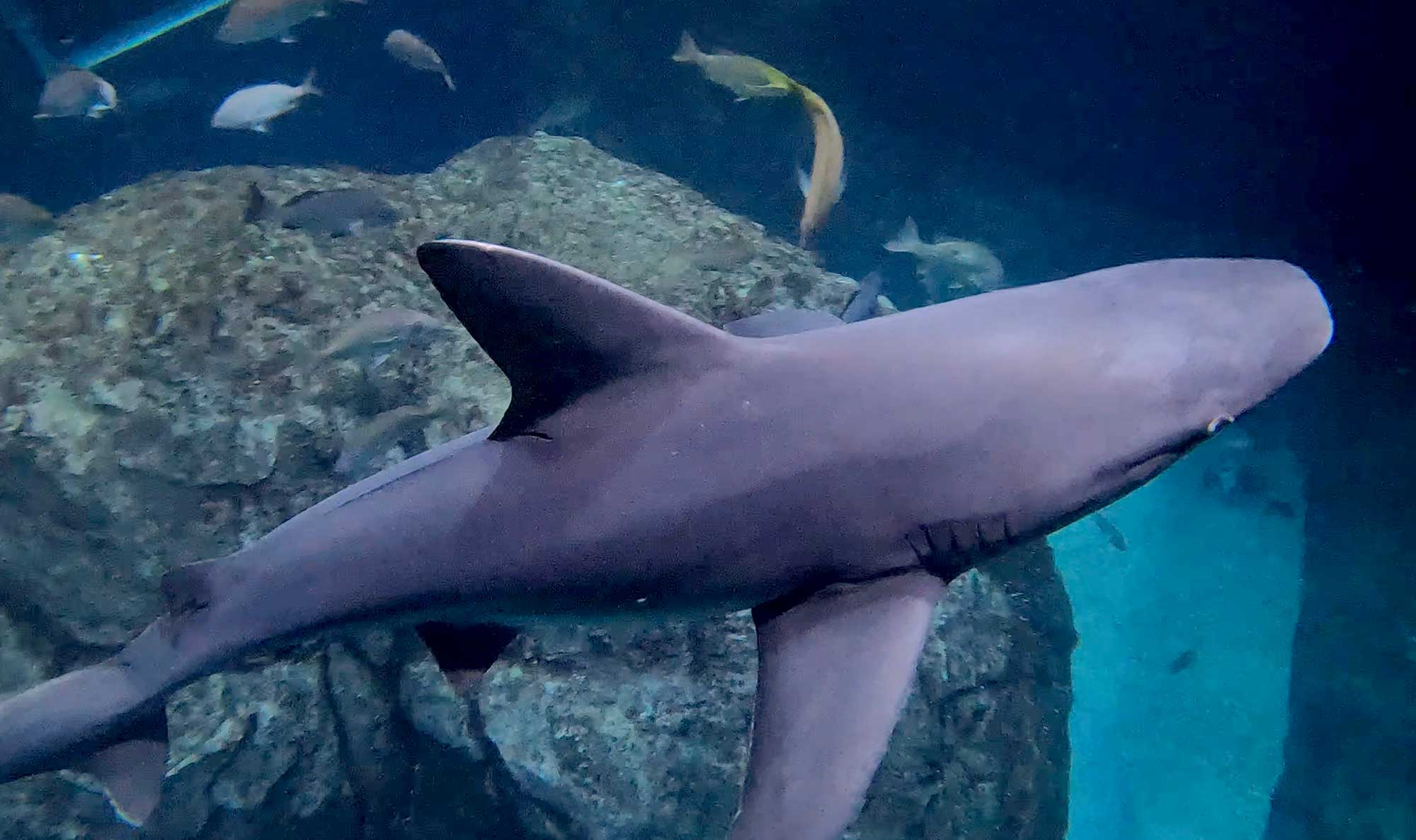

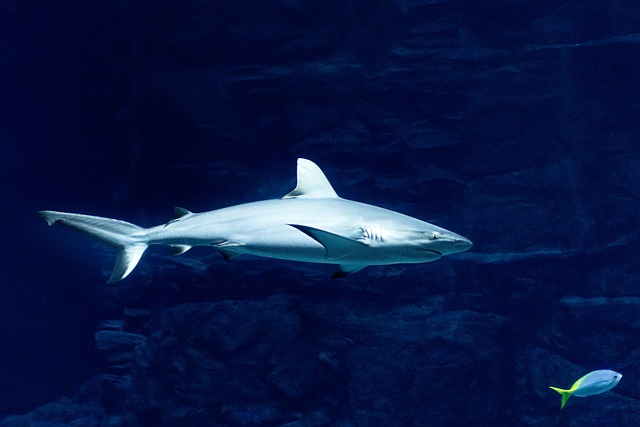

Behold the shark. They have a never-ending supply of teeth, like this sand tiger.

The scent of cafe bacon wafts through the salty sea air as the morning sun hugs the horizon. Seagulls perch on breakwater rocks, bearing witness to a new day.

“Are you guys ready?” Captain Gabe Farina asks from the stern of Kill Shot, his 40-foot charter boat.

I nod.

Farina, with tinted sunglasses and the vibes of the young and carefree, gently steers his boat out of the marina.

It’s a beautiful morning to catch a shark.

“I’m not sure where it’s rooted,” Farina, 25, tells me. “A lot of people have this lifelong goal … they want to battle this thing.”

And New Jersey — site of America’s most infamous shark attacks and the state where Peter Benchley began writing “Jaws” — just might be on the cusp of a new shark golden age.

“You’re just going to see more and more sharks,” predicts Kevin Wark, a New Jersey Marine Fisheries councilman in his 45th season fishing the Jersey Shore. “Nothing is going to chase them away.”

Including the fearsome monsters of summer blockbusters and swimmers’ nightmares.

You probably think you know sharks. Prehistoric badasses. Apex predators. Indomitable alphas of the seven seas. They’re natural-born butchers that follow no leader and abide no creed.

Or so we’ve been led to believe.

Panic at the Shore

Sharks are the perfect villain. Mysterious. Ferocious. A threat far more real than a masked bogeyman that just won’t die. The shark is everything that terrifies us. Titillates us. And exactly what we aspire to be.

So we’ve transformed a fish into an unwitting monster, victim and celebrity, something to hunt and test our will against.

We mythologized it as a blood-thirsty killing machine, exploited it for a barbaric soup, and reduced it to bloody footage for voyeurs, stuffed likenesses for tourists and cuddly if flawed narratives by some desperate to save it.

“It’s just man vs. beast,” Farina says, “and people want to conquer that beast.”

He plunges his bloody chum bucket into the ocean and drops three lines with confidence. He knows what anyone who lives and breathes this water has come to see.

Jersey fishermen are catching more sharks, bigger sharks and more dangerous sharks than they ever remember. Researchers are pulling in species they’ve never seen this far north — sharks they can’t even identify at first glance. And experts say there are probably more sharks and several more shark species swimming off our coast than at any point in the past four decades.

Sand tigers. Sandbars. And threshers. Blacktips and hammerheads enticed by rising water temperatures. Blues. Aggressive bull sharks, like the one caught in a Long Beach Island marsh in the summer of 2024. Massive makos, like the one that just jumped out of the water 50 yards from me. Even 3,000-pound great whites cruising past on their annual pilgrimage to devour Cape Cod’s seals — or the juvenile spotted a quarter mile from shore by a fishing boat just this June morning off of Island Beach State Park.

You might think there aren’t sharks here. You might say you’ve been lounging at the shore for decades and never seen a single fin. But more than a dozen species regularly spend some time off the Jersey coast. They see you. You’re just lucky the toothy bastards don’t want to be found.

Great white

(flip me!)

Great white

Your favorite animal’s favorite animal. Great white sharks are apex predators that can reach 21 feet and 4,000 pounds. Their young grow up just south of Long Island. Adults usually swim far off the coast —- but not always. “Jaws” has made us fear these majestic creatures for generations, but they do rank No. 1 globally in unprovoked attacks.

Favorite meals: Seals, dolphins, rays

And they include six of the 10 sharks most often involved in unprovoked attacks around the world, according to the International Shark Attack Files maintained at the Florida Museum of Natural History: great whites, bull sharks, sand tiger sharks, blacktips, hammerheads and spinners.

New Jersey’s 130-mile coastline has always been a border between two worlds. And on the other side of that threshold, sharks remain wildly misunderstood. Misjudged. And mistreated.

But 50 years after “Jaws” hit theaters and 109 years after the Jersey Shore was the inspiration for “Amity Island,” it’s more critical than ever that we understand them. The Northeast has experienced two fatal shark attacks in the past seven years after recording zero in the 80 years before, according to the International Shark Attack Files. Now more sharks are swimming along the Jersey coast. And they’re here to stay.

So I’m out here, vomiting off the back of this godforsaken boat, on a quixotic, seasick odyssey, a mission to tell the definitive story of the most iconic fish that ever lived — and our twisted relationship with it. It’s a universal story undeniably rooted in New Jersey.

I’ll encounter some of America’s leading shark experts, who caution that no shark story is as simple as it may seem.

I’ll learn that sharks are curious yet shy and allegedly just as afraid of us as we are of them.

I’ll visit the heart of the pro-shark movement, meet the patron saint of Jersey’s underrated sharks and ask its most recent shark attack survivor if she’s willing to forgive and forget.

And in a stunning twist of fate, I’ll witness a provoked shark attack. I’ll hear the panicked cry. I’ll see the gushing blood. I’ll come face to face with a terrified seven-foot shark, a legend that never wanted to be seen.

Lastly, I’ll question:

What kind of savage, cold-blooded monsters are we?

Charles Vansant plays in the surf in Beach Haven with a small dog when he hears frantic cries from the beach.

Suddenly, a nine-foot shark grabs him by the leg. Vansant, 23, struggles out of the water, his left leg virtually torn from his body.

The Philadelphian bleeds out within the hour.

This attack close to the beach is so far outside what scientists believe possible that initial reports are treated more like rumors.

Man-eating sharks near the coast are a “strange exception” and “sane bathers have nothing to fear,” reports the Atlantic City Daily Press.

No one can fathom what will happen next.

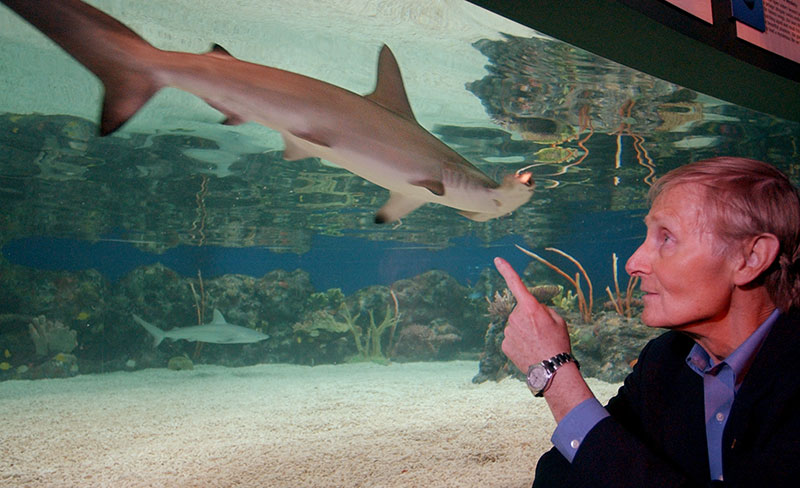

Feeding time for sand tigers at Adventure Aquarium in Camden.

Chapter II. The Comeback

A man in a red canoe needs help, she cries.

But there is no canoe.

A shark has chewed off both of Charles Bruder’s legs, turning the water crimson.

The 28-year-old hotel bell boy whispers his final words — “Shark got me” — while bleeding out in front of an estimated 500 people on the beach.

Women faint, according to The New York Times’ dispatch from the scene.

Some beachgoers are “so overcome by the horror” they need help getting back to their rooms.

An old fisherman tells the Asbury Park Press that another fatal shark attack in New Jersey “is not apt to happen again in 1,000 years.”

But it’s too late to calm growing shark paranoia.

Local officials send motorboats dangling lamb meat to lure the maneater in hopes of killing it with rifles, axes and harpoons.

The New York World captures the mood in a front page headline: “Shark hunt is on as panic spreads along N.J. coast.”

Sharks at the aquarium have their own names. And their own personalities.

Chapter III. The Villain

The 11-year-old finishes his 150th basket of the day at a local peach basket factory and heads out to skinny dip with friends in Matawan Creek.

The two previous shark attacks have been all over the papers, but the heat is oppressive and the first attack occurred some 70 miles south in Beach Haven. So the pack of sweaty boys hurl themselves off Wyckoff Dock and play in the serenity of the tall reeds.

One boy then sees what he thinks is a log floating past.

The next thing he knows, his buddy Lester is gone.

Shark hysteria is now full blown, gripping the state — and the world beyond.

The skinny dipping boys run naked down Main Street yelling, “A shark got Lester!’”

Sharks have been hunted for generations. It’s past time to understand them, experts say.

Chapter IV. The Victim

Sandbar

(flip me!)

Sandbar

Favorite meals: Bony fish, rays, crabs

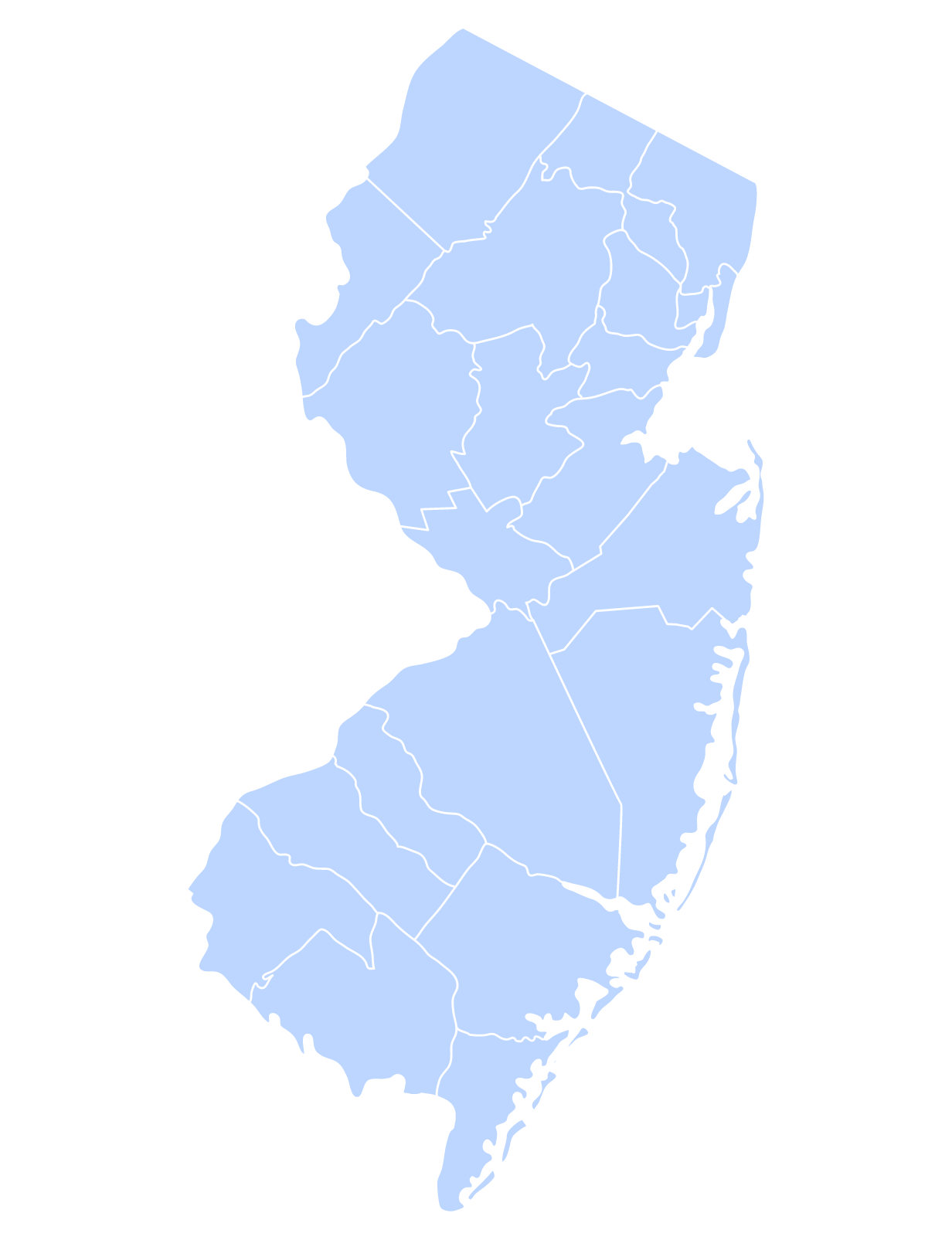

Sharks at the Shore

Explore each location to learn more.

Pennington

(credit: Associated Press)

New Brunswick

(credit: Associated Press)

Beach Haven

(credit: Mark Brown | For NJ Advance Media)

Spring Lake

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Matawan Creek

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Stone Harbor

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Cape May

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Barnegat Bay

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Delaware Bay

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Long Island

(credit: Discovery Channel)

Long Beach Island

(credit: Andy Mills | NJ Advance Media)

Island Beach State Park

(credit: Getty Images)

He’s heard Lester has been attacked and dives for the body.

Fisher, 24, finds Lester’s mangled corpse just before the shark chomps his leg, pulverizing an artery, according to eyewitness accounts.

Desperate townspeople send word up and down the creek in a frantic effort to clear it before the shark can strike again.

Many will never look at the water the same again.

Fisher dies later this evening, and Lester’s body disappears for two more agonizing days.

Sandbar sharks look scary, but they rarely bite people. They’re common in Jersey waters.

Chapter V. The Celebrity

Shortly after Lester Stillwell and Stanley Fisher are killed, it takes a bite out of New York teenager Joseph Dunn, who was swimming 400 yards away in Matawan Creek.

Dunn tries to escape, but the shark drags him under the surface twice. His friends splash the water trying to scare it and eventually pull Dunn to safety.

“I felt my leg going down its throat,” Dunn, 14, dramatically tells newspapermen from his New Brunswick hospital bed. “I believe it would have swallowed me.”

The freckle-faced kid loses nearly all the flesh from his lower right leg. But he’s lucky.

He is the only victim to survive.

Shark attacks in the open ocean were one thing. But news of three victims in a creek leaves the East Coast in shock.

Matawan’s mayor offers a $100 reward to anyone who can kill the shark. An official in nearby Keyport tries to ban swimming in the creek. Beaches are deserted up the coast and as far away as Coney Island, Brighton Beach and Rockaway.

President Woodrow Wilson discusses how to respond to the attacks in a cabinet meeting.

Geologist Bill Gordon before a fateful summer research outing in Cape May.